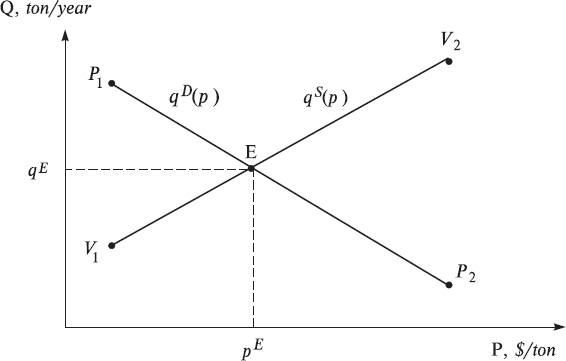

Fig. 7. Dynamics of the many-agent market economy in the price-quantity space. qD(pD) and qS(pS) are quantity trajectories reflecting dynamics of market agents’ quotations in time up to the moment of establishment of the equilibrium and making transactions at the equilibrium price.

4.4. The Classical Economies versus Neoclassical Economies

Let us call attention to the fact that, in Figs. 3 and 6, the quotation curve of the buyer, q1D (pD), has negative slope, and the slope of the quotation curve of the seller, q1S (pS), is positive. This reflects the natural desire of the buyer to purchase more at the lower price, as far as possible, and the natural desire of the seller to sell more at the higher price, as far as possible. Specifically, it is here we reveal the visual similarity of the classical economies to the known neoclassical model of S&D. But the visual similarity of picture in Figs. 3, 6 with the corresponding famous neoclassical picture in the form of two intersected lines of S&D is only formal; economic content in them is entirely different. In classical economies, this is a graphic representation of the real market process (which really occurs on the market at a given instant), while in the neoclassical economies, this picture expresses the planned actions of market agents on the market in the future. Note that in neoclassical economics it is namely the curves qS(pS) and qD(pD) that are called S&D functions. The economic content of these S&D functions can be roughly expressed thus: “the market is by itself, I am by myself”. If one price is on the market, then I purchase (or I sell) one quantity, and if it is another, then will I purchase (or I will sell) another quantity, and so forth. Thus, the market process is completely ignored in the neoclassical economic model. But we know that, in real market life, all market agents participate continuously in the market process, permanently changing price and quantity quotations, since each has made transaction price changes on the market. We will discuss neoclassical models in more detail in other chapters of the book. However, we will now develop an artificial classical economy that will be as similar to the neoclassical model as possible.

We will call this model the quasi-market economy with the “visible hand of the market” in order to distinguish it from the economies having self-organizing markets, or economies that exhibit the “invisible hand of market”. In the quasi-market economy, there is a definite chief (very strict and all-seeing by definition) of the market (visible hand of the market), to whom all agents of the market for the planned period, let us say a year, must pass very detailed and reliable plans with respect to purchase and sale of goods. These plans are compiled by agents and are given to the chief in the form of tables, which are formed according to the rule stated above. If just such a price is found on the market, then I will sell a particular volume; if it is another price, then I will purchase (or sell) another, specific volume, and so forth. These agent tables are represented in Fig. 8 for simplicity in the form of continuous straight lines, a factor which does not decrease their generality in this case.

Let us note that each agent passes its plan to the chief in the form of table, and chief itself unites data of these plans and presents them in the easy-to-use shape of the two straight lines in one picture. Common sense tells us that it is most profitable for the buyer to purchase more at the minimum price. But in this scenario the seller would want to sell less. The opposite would be true for both buyer and seller at the maximum price. Graphically, this is reflected in the fact that when point P1 is higher than point V1, and the point V2 higher than point P2, the consequence is that the slope of the curve of the buyer is be negative, and the slope of the curve of the seller, positive. It is obvious that these two straight lines will compulsorily be crossed at the point E (pE, qE), where the prices and quantities of the buyer and seller coincide. Next, the chief considers that these prices and quantities reflect certain equilibrium in the market, he or she calls the equilibrium price and quantity and declares that these values of price and quantity are set for the market year. Market process is, in this case, further completely eliminated from market life, in that the decisions of the market's chief completely substitutes it during the next year. We call this model economy a quasi-market one, since plans are compiled by market agents. However, they realize them in the prices and the quantities that are essentially dictated by the market’s chief.

Fig. 8. The classical two-agent quasi-market economy in the economic price-quantity space.

We consider this quasi-market, stationary classical economy to be, in essence, the neoclassical model of S&D. The graphic representation of the neoclassical model economy is, by the way, the same Fig. 8, since plans in the neoclassical theory are drawn up in precisely the same way that we described above for the quasi-market economy. But in neoclassical economics, it is considered a priori that the market itself in some manner will carry out the role, which the chief of the market fills in the quasi-market economy. But if the market process is absent and there are no actions of agents adapting to the market, then who or what will fill this role? Moreover, if the economy is in a stationary state, then all prices and quantities are already known to all participants in the market, and their plans then are graphically reduced simply to one point: E. It is here that the neoclassical model generally lacks any sense or value.

References

1. A.V. Kondratenko. Physical Modeling of Economic Systems. Classical and Quantum Economies. Nauka, Novosibirsk, 2005.

CHAPTER II. The Constructive Design of the Agent-Based Physical Economic Models

“The specific method of economics is the method of imaginary constructions… Everyone who wants to express an opinion about the problems commonly called economic takes recourse to this method… An imaginary construction is a conceptual image of a sequence of events logically evolved from the elements of action employed in its formation. It is a product of deduction, ultimately derived from the fundamental category of action, the act of preferring and setting aside. In designing such an imaginary construction the economist is not concerned with the question of whether or not it depicts the conditions of reality which he wants to analyze. Nor does he bother about the question of whether or not such a system as his imaginary construction posits could be conceived as really existent and in operation. Even imaginary constructions which are inconceivable, self-contradictory, or unrealizable can render useful, even indispensable services in the comprehension of reality, provided the economist knows how to use them properly. The method of imaginary constructions is justified by its success. Praxeology cannot, like the natural sciences, base its teachings upon laboratory experiments and sensory perception of external objects… The main formula for designing of imaginary constructions is to abstract from the operation of some conditions present in actual action. Then we are in a position to grasp the hypothetical consequences of the absence of these conditions and to conceive the effects of their existence… The method of imaginary constructions is indispensable for praxeology; it is the only method of praxeological and economic inquiry”.

Ludwig von Mises. Human Action. A Treatise on Economics. Page 236