Pemicka£., 1993. Analytisch-chemische Untersuchungen an Metallfunden von Uruk-Warka und Kis // Müller-Karpe H. Metallgefàsse im Iraq I. Prâhistorische Bronzefunde. Abt. II. Bd. 14. Stuttgart.

Philip G., Clogg P.W., Dungworth D.,2003. Copper Metallurgy in the Jordan Valley from the Third to the First Millennia B.C.: Chemical, Metallographic and Lead Isotope Analyses of Artefacts from Pella // Levant. № 35.

Piggot C.,1999. A Heartland of Metallurgy. Neolithic/Chalcolithic Metallurgical Origins on the Iranian Plateau // Der Anschnitt. Beiheft 9. Bochum.

Potts T.,1995. Mesopotamia and the East. An Archaeological and Historical study of Foreign Relations ca. 3400–2000 BC // Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. Monograph 37. Oxford.

Pulszky T. von,1884. Die Kupferzeit Ungam. Budapest.

Ravich I.G., Shemakhanskaya M.S.,2005. On the Problem of Gomogenization and Corrosion of Copperarsenic Alloys // Metallurgy: a Teuchstone for cross-cultural Interaction. Abstracts of International Archaeometallurgy Conference. London.

Rovira S., Games P.,1993. Las primeras etapas metalurgicas en la peninsula Ibérica. Estudios metalograficos. Madrid.

Shalev S.,1988. Redating the Philistine Sword at the British Museum: a case Study in Typology and Technology // Oxford Journal Archaeology. № 7.

Shalev S., Goren J., Levy T.,1992. A chalcolithic Mace Head from the Negev Israel: technological Aspects and cultural Implication // Archaeometry. Vol. 34. № 1.

Shalev S.,1995. Metals in Ancient Israel: Archaeological Interpretation of Chemical Analyses // Israel Journal of Chemistry. Vol. 35. № 2. Jerusalem.

SmithC.5., 1968. Metallographic Study of Early Artifacts Made from Native Copper // Actes du XI Congres International d’Histoire des Sciences. Wroclaw-Varsovie-Cracovie. V. VII.

Smith C.S.,1973. An Examination of the Arsenik-rich Coating on a Bronze Bull from Horoztepe HApplication of Science in the Examination of Works of Art. Boston.

TadmorM., Kedem D.,1995. The Nahal Mishmar Hoard from the Judean Desert: Technology, Composition and Provenance HAntiqot. Prehistoric, Protohistoric and Bronze Age Studies. Jerusalem. V. XXVII.

Talion E,1987. Métallurgie susienne I. De la fondation de Suse au XVIII esiècle avant J.-C. Paris.

Thomsen G.J.,1836. Ledetraad tit Nordick Oldkindighen. Kobenhavn.

ToblerAJ.,1950. Excavations at Tepe Gawra. Philadelphia.

Waetzoldt H.,1990. Zur Bewaffnung des heeres von Ebla // Oriens Antiquus. № 29.

Wayman M.L., Duke1999. The Effect of Melting on Native Copper // The Beginning of Metallurgy. Der Anschnitt, Bochum.

Wertime T.A.,1964. Man’s First Encounters with Metallurgy // Science. V. 146. № 3649.

Worsaae J.J.,1843. Danmarks oltid oplyst ved Oldsager og Gravhoje. Kobenhavn.

Yalçin Ü., Pemicka E.,1999. Frühneolithische Metallurgie von Asikli Hôyük // Der Anschnitt. Beiheft 9. Bochum.

Potentials of metallography in investigations of early objects made of copper and copper-base alloys (The Early Metal Age)

N.V. Ryndina

Resume

Application of methods of optical and electronic metallography in investigations of early copper and copper-base alloys enables us to solve the questions that are far beyond the investigational field traditionally covered by the history of metallurgy. These refer to revealing the modes of metalworking developed in different cultures and production units; establishing dependence between the metalworking technology and the raw material used; analysis of the raw material from the standpoint of metallurgical processes taking place when producing it; investigation of the problem of production structure and organization, and so forth. Among the problems studied with the help of metallography of special importance is that one concerning regularities in the progress of earliest metallurgical knowledge. Over 500 microstructural analyses are discussed in the work; they form the investigational base for considering the production dynamics in the Near East and South-Eastern Europe, that is, how more and more complicated regularities can be observed in their development stage by stage from the Eneolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Special attention is paid to the metalworking technologies that permit to discriminate between the Neolithic and the Eneolithic. In conclusion the author raises the question concerning interaction of primary and secondary centres of metal production on the example of the metallographic analyses carried out on the metal samples of Maikop culture of the North Caucasus.

И. Гошек

Проблемы изучения сварных швов с высокой концентрацией никеля в археологических железных изделиях

Перевод Л.И. Авиловой

Введение

В ходе археометаллургических исследований ранних железных предметов с территории Чехии выявлено значительное число находок, у которых между перлитными и мартенситными структурами расположены сварные швы. Структуры этих швов обычно обогащены никелем и в меньшей степени кобальтом. Сварные швы легко различимы при микроскопическом исследовании и хорошо поддаются химической обработке, в результате чего могут быть получены данные, характеризующие использованное сырье и технологические приемы его обработки, что крайне важно при археометаллургических исследованиях.

Никель в сварных швах

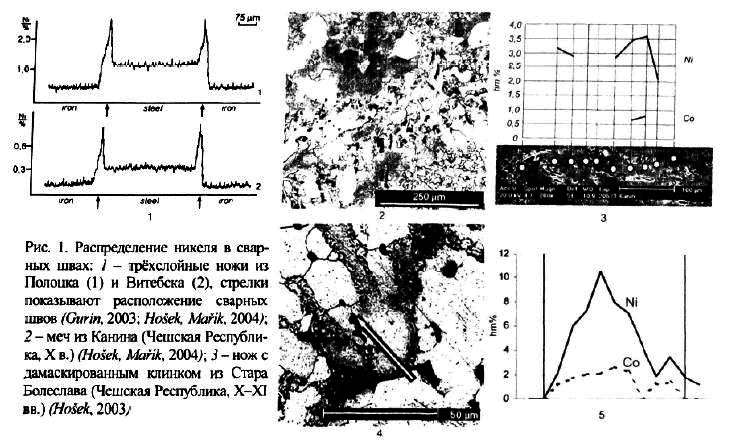

Присутствие никеля в сварных швах объясняется достаточно просто. Железо в разогретом металле окисляется интенсивнее, чем такие элементы, как никель, кобальт, мышьяк или медь. Эти более благородные, чем железо, металлы находятся в дисперсном состоянии под окисленной поверхностью предмета. В процессе сварки двух разогретых полос железа повышенная концентрация никеля может проявиться в сварном шве, однако впоследствии, при многократном нагреве поковки, концентрация никеля понижается в результате его диффузии. Кроме никеля, швы обычно обогащены углеродом. Поскольку содержание никеля понижается при температуре перехода к структуре аустенита, углерод переходит из участков феррита, где никель отсутствует, в структуру аустенита, обогащенную никелем, в результате чего формируется структура перлита или даже мартенсита. Так, мартенсит (без дополнительной закалки) возникает при концентрации никеля в железе свыше 7 %. Никель часто сопровождается кобальтом, но в менее высоких концентрациях. Распределение этих элементов в сварных структурах неодинаково. Их содержание нарастает от краев обогащенной зоны к ее центру, где достигает максимума, Ni 1-10 % (рис. 1). Известны сварные швы с содержанием Ni свыше 15 % и даже 20 %. Концентрация кобальта обычно не превышает 2 %. Высоконикелевые зоны обычно имеют вид полос, часто встречаются и зоны неправильной формы. Участки с наибольшей концентрацией никеля могут располагаться на различных отрезках сварных швов.

На рис. 2 показаны высоконикелевые швы. Топор из Бреслав-Поганско (IХ-Х вв.) имеет однолинейный шов с 11.2 % Ni (рис. 2, 1),сверло из того же памятника (рис. 2, 2) демонстрирует шов в виде нескольких линий с 19.2 % Ni и 1.2 % Со. В подкове из Ровенско (около XV в.) концентрация никеля варьирует: в сварном шве (рис. 2, 3) 3.4 % Ni и около 1 % Со, на другом участке того же шва (рис. 2, 4)уровень содержания этих элементов ниже порога чувствительности микроскопа ЕВАХ. Обломок железного предмета из замка Троски имеет 28.5 % Ni в поверхностном слое (рис. 2, 5), тогда как внутренние сварные швы содержат не более 10 % Ni (рис. 2, б). Локальное содержание никеля может достигать сверхвысоких значений, как на проушном топоре из Ветржно-Бобрка (Польша) — 39.1 % Ni на одном из участков.