Jenny Ferret was a good-natured old thing. She said Xarifa and Tuppenny deserved a treat – that they did! and Sandy agreed with her. So he consulted Tappie-tourie, the speckled hen. Tappie-tourie talked to the sparrows who roost in the ivy on the walls of the big barn. And the sparrows twittered through the granary window, and talked to the mice, behind the corn-bin. They told the mice that it would be quite – quite – safe, on Sandy’s word of honour, to tie themselves up in a meal bag, which Sandy would carry to the caravan.

In the meantime Jenny Ferret had made preparations for a mouse party; cake, tea, bread and butter, and jam and raisins for a tea party; and comfits, and currants, lemonade, biscuits, and toasted cheese for a dance supper party to follow. She brewed the tea beforehand, because the teapot would be too heavy for the dormouse; so she covered it up with a tea-cosey. Then she unfastened Xarifa’s cage and Tuppenny’s hamper, and the string of the meal-bag; bolted the windows of the caravan, and came out; she locked the door on the outside, and gave the key to Sandy. Sandy had business elsewhere; and Jenny Ferret was quite content to spend the night curled up in a rug on top of the caravan steps, listening to the merriment within.

And a merry night it was! One of the mice had brought a little fiddle with him, and another had a penny whistle, and all of them were singers and dancers. They came tumbling out of the bag in a crowd, all dusty-white with meal. No wonder Sandy had found the sack rather heavy! There were four visitor mice from Hill Top Farm, and five from Buckle Yeat and the Currier; and there were no less than nine from Codlin Croft.

While they tidied and dusted themselves, Xarifa brushed Tuppenny’s hair. When they were all snod [47] and sleek, she peeped under the tea-cosey, “The tea is brewed, we will lift the lid and ladle it out! I will use my best doll’s tea service. Please, Pippin and Dusty, sing us a catch, while Tuppenny and I set the table. First we will have songs and tea, and then a dance and a supper, and then more singing and dancing, and you won’t go home till morning!”

Pippin clapped his little paws, “Oh, what fun! how good of old Jenny Ferret, to cheat the pig-stye cat!” And he and Dusty sang with shrill treble voices—

“Dingle, dingle, dowsie! Ding, dong, dell!

Doggie’s gone to Hawkshead, gone to buy a bell!

Tingle, ringle, ringle! Ding, dong, bell!

Laugh, little mousie! Pussy’s in the well!”

Then Cobweb sang, “Who put her? Little Tommy Thin!” and Pippin repeated,“Who put her in? Who pulled her out?” (“Who put her in?” chimed in Dusty.) “Who pulled her out? Little Tommy Stout!” sang Smut. (“Who pulled her out?”) Then all the mice sang together—

“What a naughty boy was that,

For to drown our pussy cat;

Who never did him any harm,

And caught all the mice in Grand-da’s big barn!”

“But Pussy did not catch quite all of us!” laughed Pippin. He started another glee—

“Dickory, dickory, dock! the mouse ran up the clock!”

(Each mouse took up the song a bar behind the last singer – Dickory, dickory, dock!) The clock struck one – (The mouse ran up the clock) Down the mouse run – (The clock struck one) Down the mouse run – dickory, dickory, dock!

There was singing and laughing and dancing still going on in the caravan when Sandy came back in the morning.

CHAPTER XXI

The Veterinary Retriever

Now while the mice were merry-making in the caravan, all sorts of things were happening in the stable. Paddy Pig continued to be feverish and restless; he kicked off the blanket as fast as the cats replaced it. “His strength is well maintained,” said Cheesebox after a renewed struggle, “we must keep him on a low diet.” “What! what! what? I’m hungry,” squealed the patient; “fetch me a bucketful of pig-wash, I say! I’m hungry!” “Possibly he might be granted a teeny weeny bit of fish; the fisher-cart comes round from Flookborough on Wednesdays,” purred Mary Ellen. “I won’t eat it! flukes are full of pricky bones. Fetch me pig-wash and potatoes!” “I could pick it for you if you fancied a little fish—” “I don’t want fish, I tell you. I want potatoes!” grumbled Paddy Pig. He closed his eyes and pretended to snore. “He sleeps,” purred Mary Ellen. “Which of us shall sit up first? We might as well take turns,”said Cheesebox, who was growing a trifle tired of Mary Ellen’s purring. “I will watch first, dear Cheesebox, while you take forty winky peepies.”

Mary Ellen composed herself beside Paddy Pig with her paws tucked under her. Paddy Pig sulked. Maggret, the mare, dozed in the stall nearest to the window. There was some reflected moonlight through the small dusty panes, but the stable was very dark.

Cheesebox jumped nimbly onto the manger, and thence into the hay-rack, wherein was some foisty [14] hay, long undisturbed, to judge by three doubtful eggs in a forgotten hen nest. Cheesebox curled herself up in the hay. Over head cobwebs hung from the broken plaster of the ceiling; there were cracks between the laths, and holes in the floor of the loft above.

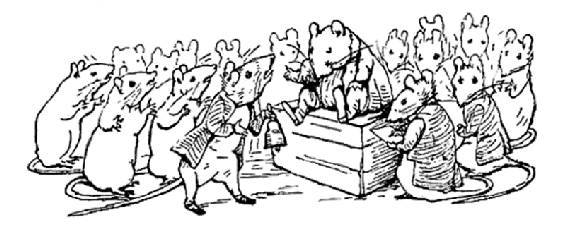

The stable had been well appointed in old days. The tailposts of the stalls were handsomely carved, and on each were nailed the antlers of deer. The points served as pegs for hanging up the harness. But all had become neglected, broken, and dark; the corn-bin was patched with tin, and the third backmost stall was full of lumber. A slight noise amongst the lumber drew the attention of Cheesebox; a climbing, scratching noise, followed by the pattering of rat’s feet over the loft above. Mary Ellen, in the stall below, stopped purring. Cheesebox listened intently. There were many pattering footsteps. More and more rats were assembling. “There must be a committee meeting; a congress of rats,” thought Cheesebox, very wide awake. The noise and squeaking increased, until there was a sound of rapping on a box for silence. “I move that the soapbox-chair be taken by Alder-rat Squeaker. Seconded and carried unanimously.” “First business?” said old Chair Squeaker, in a rich suetty voice. “First business, please?” But there seemed to be neither first nor last; all the rats squeaked at once, and the Chair-rat thumped in vain upon the soapbox. “One at a time, please! You squeak first! No, not you. Now be quiet, you other rats! I call upon Brother Chigbacon to address the assembly. Now, Brother Chigbacon, squeak up!” “Mr. Chair-rat and Brother Rat-men, I rise from a sense of cheese – I should say duty, so to squeak. I represent the stable rats, so to squeak, what is left of us, so to squeak, being only me and Brother Scatter-meal. Mr. Chair-rat, we being decimated. A horrid squinting, hideous old cat named Cheesebox—” (Mary Ellen looked up at the hay-rack and grinned from ear to ear; Cheesebox’s tail twitched) “—a mangy, skinny-tailed, scraggy, dirty old grimalkin, is decimating us. What is to be done, Mr. Chair-rat and Brother Rat-men? We refer ourselves to the guidance of your united wisdom and cunning!”

The loud, noisy squeaking recommenced; all the rats squeaked different advice, and old Chair Squeaker thumped upon the soapbox. At length amongst the jumble of squeaks, a resolution was put before the meeting by Ratson Nailer, a pert young rat from the village shop. He proposed that a bell be stolen and hung by a ribbon round the neck of that wicked green-eyed monster, the ugliest, greediest, slyest cat in the whole village; “But with a bell round her neck we would always hear her coming, in spite of her velvet slippers.”