The orchard which gives Codlin Croft Farm its name is a long rambling strip of ground, with old bent pear trees and apple trees that bear ripe little summer pears in August and sweet codlin apples in September. At the end nearest to the buildings there are clothes-props, hen-coops, tubs, troughs, old oddments; and pig-styes that adjoin the calf hulls [21] and cow byres. The back windows of the farmhouse look out nearly level with the orchard grass; little back windows of diamond panes not made to open. The far end of the orchard is a neglected pretty wilderness, with mossy old trees, elder bushes, and long grass; handy for a pet lamb or two in spring, and for the calves in summer.

At this time of year, a north country April, the pear blossom was out and the early apple blossom was budding. The snowdrops that had been a sheet of white – white as the linen sheets bleaching on the drying green – had passed; and now there were daffodils in hundreds. Not the big bunchy tame ones that we call “Butter-and-eggs,” but the little wild daffodillies that dance in the wind. Through the broken gate at top of Codlin Croft orchard came Pony Billy with the caravan. He drew it up comfortably in shelter of Farmer Hodgson’s haystack, which stood, four-square and prosperous, half in the orchard and half in the field. “Only, Jenny Ferret, if I put the caravan here you must promise not to light a fire. We must not burn Farmer Hodgson’s hay for him.” “And how will I boil the kettle without a fire? Take us further down the orchard near the well, behind the bour-tree [03] bushes.” “All right,” agreed Pony Billy, pulling into the collar again; “perhaps it would be safer. I can come up to the stack by myself for a bite.”

“Cluck-cur-cuck-cuck!” said Charles, “I recommend that flat place between the pig-stye and the middenstead.” [31] “Yes, indeed, cluck, cluck! there are lots of worms if you scratch up the manure,” clucked Selina Pickacorn. “Are they going to put up a tent?” asked the calves. “Oh, yes, lots of nice red worms,” clucked Tappie-tourie and Chucky-partlet. “What’s that funny old woman they call Jenny Ferret? she has got whiskers?” asked an inquisitive cat, sitting on the roof of the pig-stye. “Quack, quack! stretch your long neck and peep in at the window, Dilly Duckling.” “I cannot see; quack quack; I cannot see anything through the curtains.” “Gobble-gobble-gobble!” shouted the turkey cock, strutting after Charles. Sandy curled his tail tightly; “Go further down beyond the bour-tree bushes, Pony William, further away from the farmyard.” When the caravan had been drawn into position, it became necessary for Sandy to do a large loud determined barking all round, in order to disperse the poultry.

After pitching camp in the orchard Pony Billy and Sandy held an anxious consultation, “Did you notice anything while we were coming through the wood?” “Yes. Pig’s trotter marks.” “How many times did we go round and round that hill, Pony William?” “We would be going round it yet, if I had not gone widdershins.” [59] “What shall we do about Paddy Pig?” “I am going back to fetch him.” “What! into Pringle Wood?” “Yes,” said Pony Billy; “but first I want a saddle and bridle. And look whether my packet of fern seed is safe; for I shall have to go amongst the Big Folk in broad daylight.”

ROY, BOBS, AND MATT WERE LYING LAZILY IN THE SUN.

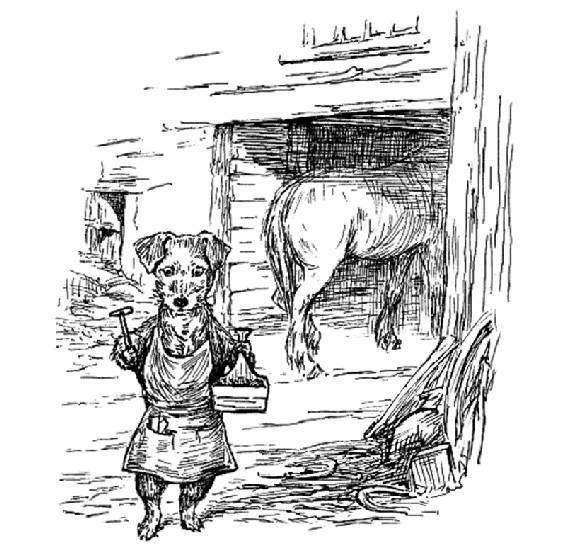

Pony Billy borrowed several things, by permission of the farm dogs, Roy, Bobs, and Matt, who were lying lazily in the sun before the stable door. He asked for the loan of a nosebag containing chopped hay, and straw, and uveco [56]; also for two pounds of potatoes; and a saddle and bridle, and for the chest-strap with brass ornaments belonging to the cart harness. There were four brass lockets on the strap; a swan, a galloping horse, a catherine wheel, and a crescent. The last named is a charm that has been worn by English horses since the days of the crusaders. The strap was too long; it swung between his knees; but Pony Billy felt fortified and valiant. “Do you think you will be chased?” asked the dogs. “I shall not. I am going to the smithy to have my shoes turned back to front.” “Our mare Maggret is at the smithy,” said Bobs. “You will have to go past the back door and the wash-house if you want potatoes,” said Matt. “Nobody can see me,” said Pony Billy. He clattered across the flags, bold in possession of fern seed and invisibility. Mrs. Hodgson, inside the house, called to her maid-servant, “Look out at the door, Grace; is that the master I hear coming home with the mare?” “I hear summat, but I see nought,” answered Grace, perplexed.

“I AM GOING TO THE SMITHY”

Pony Billy started on his quest. The farm dogs went to sleep again in the sun.

Sandy with his tail uncurled trailed back disconsolately to the orchard camp. The ducks and calves had wandered away; but Charles and his inquisitive hens were still in close attendance, and conversing endlessly.

The conversation was about losing things. Xarifa’s scissors were missing. Jenny Ferret as usual suspected Iky Shepster, the starling. He was not present to deny the charge; he had flown off foraging with the sparrows.

“Losses,” said Charles, sententiously, “losses occur in the best regulated establishments. Likewise finds; but finds are less frequent; and, therefore, more noteworthy. One afternoon I and my hens were promenading in the meadow. I heard Tappie-tourie – that bird with the rose comb [40] – clucking loudly in the ashpit. I inquired of Selina Pickacorn whether Tappie-tourie had laid an egg? Selina replied that it seemed improbable, as Tappie-tourie had already laid one that morning in the henhouse. But hens are fools enough to do anything; I ordered Selina to proceed to the ashpit, to ask Tappie-tourie whether she had laid a second egg or not. When one hen runs – all the other hens run too; being idiots; cluck-cur-cuck cuck cuck!” “Oh, Charles! Charles!” remonstrated Selina and Chucky-partlet coyly. “Aggravating idiots,” repeated Charles, who did not believe in encouraging pride amongst female poultry. “As the whole of my hens continued to cluck in the ashpit in total disregard of my commands to come out – I stalked across the field, and I looked in. I said, ‘What are you doing, Tappie-tourie? you are a perfect sweep. Selina Pickacorn, you are equally dirty. Chucky-doddie, you are even worse. Come out of the ashpit.’ They replied, all clucking together – ‘Oh, Charles! do look what a treasure we have found! But none of us know how to stick it on, because it has no safety-pin.’ They showed me Mrs. Hodgson’s big cairngorm [05] brooch that had been missing for a fortnight. They asked me if it was worth a hundred pounds. Cock-a-doodle-doo! A hundred pounds, indeed!” said Charles, swelling with scorn. “I told them it was absolutely worthless to us who wear no collars; not worth so much as one grain of wheat; cluck-cur-cuck cuck cuck! Hens always were noodles, and always will be. Ask them to tell you the tale of the demerara sugar.”

“That?” said Selina Pickacorn, quite unabashed, “oh, that happened long ago when we were inexperienced young pullets. Besides, it was all along of the parrot.” “Pray explain to us the responsibility of the parrot?”said Sandy. Five or six hens all commenced to cluck at once. Charles interjected cock-a-doodles. Consequently their explanation became somewhat mixed. Therefore it must be understood that this story – like the corn in their crops – is a digest.

CHAPTER XIV

Demerara Sugar

Upon fine days in spring the parrot’s cage was set out of doors upon top of the garden wall, opposite the farmhouse windows. In the intervals of biting its perch and swinging wrong-side up, the parrot addressed remarks to the poultry in the yard below. The words which it uttered most frequently in the hearing of those innocent birds were, “Demerara sugar! demerara sug! dem, dem, dem, Pretty Polly!” The chickens listened attentively.