It took them until the following evening to cross the marsh and somehow this time it did not seem so terrifying. They saw no goblins and although they went along the same path as that by which they had travelled before there was no trace of Golconda nor of the tree on which he had been left. They emerged out of the mists of the marsh into a calm golden evening at a place some way from that by which they had entered when they came. They stood for a little while looking out over a landscape of rolling foothills gently sloping upwards towards distant moors. It was the end of spring and the beginning of summer, and the trees, huge elms and sycamores and ash, were covered in a multitude of different greens from the deep dark emerald of the elms to the delicate lime green of the ash trees. They towered up into the blue, their leaves gently moving in the evening breeze; rows of them like giant guardians of the earth stretching along the narrow valleys between the hills where little streams gurgled their way down through banks laden with primroses and bluebells and little green shoots of bracken poked their way up through the rich dark peat moss.

Faraid turned to them and pointed to a little hummock on the skyline.

‘There is your first Scyttel. From there you will know your way to the lair of the mountain-elves by the feeling of the Roosdyche. Farewell, and may Ashgaroth guide you safely to the journey’s end.’

So saying he turned and quickly vanished into the mists of Blore so that even as they looked after him, he was gone. Then they looked at one another in silence for a few moments before Perryfoot pricked up his ears.

‘Come on, ’ he said. ‘It’s spring and the earth is full and green, ’ and he set off up the slope with the others following behind.

CHAPTER XIX

It was a perfect evening as they made their way up the green bank alongside the stream towards the Scyttel in the distance. The air was warm and scented with bluebells which covered the ground under the giant trees in a blue haze, and further down, near the stream, there were splashes of vivid orange from the marigolds that sprang up in clusters wherever there was a marshy piece of ground. The sun was almost down behind the far hills but it seemed to shine with a particular fierceness as if hoping that its light would last after it had gone so that its warm, magic glow flooded the little valley along which they were walking and sent shafts of gold through the huge green leafy tree canopies overhead. Then, suddenly, it was gone and the shadows of dusk filled the valley and soon the dew fell everywhere and their feet became wet as they walked through the long grass. The dampness on the ground filled the air with the smell of wet green leaves and grass: the unmistakable smell of a spring evening, and the animals drank it in as if it were elvenwine and indeed it had the same effect, filling their tired bodies with fresh energy and vigour so that they felt they could have walked for ever. The air stayed warm late into the night and a little breeze came up, blowing gently against their faces as if it was trying to cleanse their memories of that last morning on Elgol. The agony of walking without Sam was almost more than they could endure. They would keep forgetting he was not there and then, on turning to speak to him or look for him, would once again be hit by the shock of realizing what had happened. If it was worse for any of them, then it was worse for Brock, because he had known the dog the longest and had walked alongside him for the whole of the journey. Nab had asked Perryfoot to walk with him and the hare had willingly obliged but it did not seem to have helped much; the badger would walk along with his head down and then suddenly look up and stare at Perryfoot with blank, uncomprehending eyes until he remembered and then his head would once again slump down and he would urge his tired body to resume its shuffling gait over the grass. First Bruin, then Tara and now Sam; they had all felt the losses terribly, particularly Nab, whose life had been so intertwined with Brock’s, but it was undeniably hardest on the badger, for two of them had been his family and one his best friend and Nab now had Beth to live for so that he was able to look forward: for Brock the past had died and the future was uncertain and lonely.

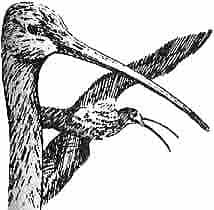

They reached the mound that night and slept under the shade of a huge sycamore until the following evening when they awoke feeling refreshed after a deep dreamless sleep. Even Brock felt a bit better as they started out once again towards a range of mountains in the far distance. They were quite high now and they walked through green fields cropped short by grazing sheep which were criss-crossed by white stone walls. High up in the clear blue sky larks sang while lower down plovers dipped and swooped over the ground and curlews sent out their liquid warbling cries into the still evening air. Behind them, from the valleys through which they had walked the previous night, they heard the occasional screech of an owl or the bark of a fox or else a cuckoo calling out his spring song. The daisies and dandelions which in the heat of the day had sprinkled the meadows with whites and oranges were now closing up and drawing their petals in for the night.

On they walked throughout the remainder of the spring; then summer came, and the hot sun beat down on them, making their throats dry and parching their mouths so that they walked from stream to stream, but as the days wore on and rain refused to fall the ponds and streams got low and the water that was left in them was brackish and musty. They were still making for the far mountains, which appeared hazy and bluish in the distance, but they had dropped down again now into the lowlands where there was little if any breeze to relieve the unrelenting heat which poured down from the blue sky into the lanes and between the hedges along which they cautiously made their way. They slept only in the afternoons now for Nab was anxious that they should move as quickly as possible and he and Beth each carried a share of her winter clothes: the brown cape and the jerseys which had helped her to survive the cold. Nab had wanted her to bury them under a hedge somewhere but she had been adamant in her refusal.

‘They’re all I have left of my old life,’ she had said, ‘and of my home. I could no more part with these than you could throw away your bark from Silver Wood.’

So, because he loved her, he reluctantly agreed and had ended up carrying her heavy cape and two jerseys while she took the remaining one and thanked him for being so thoughtful and kind.

It was in the height of summer, one hot morning when they were trudging along a dry dusty cattle track through a field, that they saw for the first time a thick black column of smoke rising in the distance. It went straight up in the humid windless air and the animals could smell the acrid stench of its fumes from where they were standing. They stopped still and looked at it; they had all seen smoke before from the chimneys of the Urkku but this was somehow different. The smoke was blacker, thicker and more dense, and the smell was sickly-sweet and nauseating; it reminded Beth of the smell caused when people put chicken carcasses on fires to burn them after the Sunday dinner.

‘Look, there’s another,’ Brock said, and he pointed to a thicker column round to their right and as they looked around they saw more and more until there must have been a dozen fires, all with their black plumes drifting up into the sky. There was something ominous and evil about them and Nab felt a chill go down his back as he watched.