‘But no one saw us,’ said Nab. ‘We took the greatest care. How could they know we are here?’

The heron laughed; a deep rasping noise which seemed to grate its way up from the bottom of his legs.

‘You cannot escape the eyes of Dréagg. His spies are everywhere. He knew where you were from the moment you left your wood. Do not underestimate him. Now follow me, but be extremely cautious. There is but one way through the marshes. If you step off the way you will swiftly be submerged in the ooze.’

They set off through the marsh, each of them following exactly in the footsteps of the other except for Warrigal, who once again sat perched on Nab’s shoulder. As they walked Nab asked the heron why he was unable to feel the Roosdyche here.

‘It is because Dréagg has blighted this place,’ Golconda said. ‘It belongs to the goblins who have no need for light nor for the power of the earth. Ashgaroth and his gifts are unknown here, it is an empty space for him and does not exist. Can you not feel the Evil One all around you?’

‘Why do you then stay?’ asked Warrigal.

‘I have told you; someone must show travellers across. There is no other way to the sea without going through an enormous detour over the high mountains and that would take far too long and be even more dangerous. In any case it is impassable in winter. And I can survive on what is to be found in the marshes. The goblins do not suspect that I work with the elves; I am a solitary bird and they leave me alone. I am too unimportant for Dréagg to waste his efforts on so I stay and no one bothers me. That is the way that it has been.’ He paused while they walked under the overhanging branches of a small oak tree which swept down almost to the ground. The trunk of it was covered in thick green lichen, and on the roots which stuck up out of the green sludge, grew hundreds of little orange fungi that contrasted strongly with the dull greens and browns all around.

‘But you,’ Golconda went on. ‘I know all I wish to know about your journey and your mission and I bid you the greatest of good fortune for you will need it. But tell me of your wood and of the animals in it, and of your early days, Nab; and the Urkku with you, who is of the Eldron: tell me of her. I see that she speaks to you in our tongue. I would like her to talk to me of the ways of the Urkku.’

The time passed quickly as they talked; they forgot the evil around them as they related the stories and legends of Silver Wood to the heron, and when Nab told him of the early days, sunshine and laughter seemed to fill his mind. But when they got to the end the heron stopped them and asked Beth to tell him of her life and they listened in fascination and amazement as she told them haltingly of how she had lived and of the ways of man.

They enjoyed talking to him for he was a good listener, only occasionally interrupting to ask a pertinent question or add some observation of his own. He reminded them all, in his stature and bearing, of Wythen and they wondered sadly if they would ever see the old owl again. Soon, before they realized it, the darkness began to fall and night started to set in.

‘We must press on, make haste,’ Golconda said when Warrigal asked him if they were going to rest for the night. ‘There is no knowing what the goblins are planning, and the sooner you are safely through the marshes, the better I shall feel.’

The swirling, writhing mist had not lifted all day but the darkness made it appear thicker and more dense so that it felt like a heavy drizzle and their coats once again became soaked with wet. They went in silence now, concentrating on following the heron as he walked ahead of them for they could see very little. Suddenly Nab, who was immediately behind him, heard a muffled thud and a little cry which was stifled almost as soon as it began so that he could not be certain whether or not he had imagined it. He stopped for a second and whispered to Warrigal.

‘Did you hear that?’

‘Yes,’ the owl replied quietly.

‘What was it?’

‘Just some creature, I would think. I heard a splash as well. Come on or we’ll lose sight of Golconda.’

Nab peered ahead through the murk. For an instant or two he could see nothing except the shapes formed by the mist but then to his relief he saw the familiar form of the heron, striding ahead, his tall white figure appearing almost wraith-like as it gathered shrouds of mist around it.

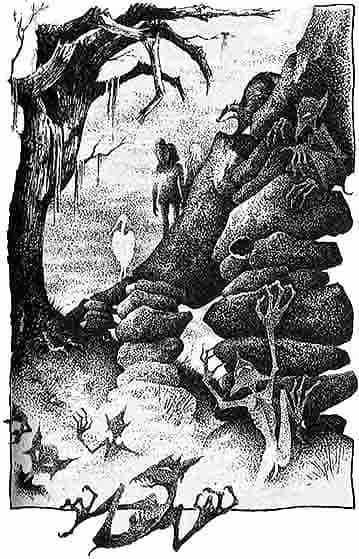

‘Hurry up,’ said Warrigal urgently and Nab felt the talons of the owl tighten on his shoulder. ‘He seems to have got a long way in front. Better not call him in case the goblins are around. Come on.’ Nab moved forward quickly and the others followed and soon they were once again trudging along in silence, sunk in thought, with the heron just visible in front. The little nagging feeling of panic which Nab had felt when he had heard that cry soon passed as he concentrated on following Golconda. Nevertheless there was still something bothering him and as time went on and the figure ahead of him kept going forward resolutely without ever turning around or getting any closer, Nab felt little prickles of fear creep up his spine until he felt as if the hair on the back of his neck was standing on end. Nomatter how quickly or how slowly they walked the heron always seemed to remain exactly the same distance in front of them. Why did he not wait for them to catch up? If only he would turn round and they could see his face or if he would just say something. The marsh seemed to be getting thicker and thicker and the smell of damp rotting vegetation was now so heavy on the air that they could almost see it lying like a cloud above the surface of the dark brackish waters and bog moss which lay on each side of their raised path. Around I them the swirling clouds of damp played tricks with their eyes, making it seem as if the dead stumps of the trees were moving; every so often one would loom up at them out of the mist like some malevolent creature of the hog.

Nab’s eyes were fixed so much on the figure ahead of him that he failed to see the ending of the path. Suddenly his feet were enclosed in a mass of green sludge and when he tried to lift them out he found that it was impossible; the more he tried to free one, the further in did the other one sink. Warrigal had flown back on to the path and he called to the others to hurry up. Beth was only just behind but by the time she had arrived the quaking mire was up to his knees. Brock, Sam and Perryfoot ran the few paces to the spot where the path fell away into the bog and saw with horror the scene before them as Nab frantically waved his arms about trying to throw himself towards the bank, but the more he struggled the further he sank. He could feel himself being sucked down with a strength that was impossible to fight: soon he could not move his legs at all for the sludge was halfway up his thighs. Beth lent over as far as she could but still she could not reach his hand and then, through the haze of her memory, she recalled scenes from films and books in which someone had been caught in quicksand. Quickly she took off her cape and rolled it on the grass so that it formed a rope of cloth and then she lay face down on the path as near to the edge as she dared until the stench of the bog filled her nostrils.

‘Brock, let me hold on to you and Sam, you lie across my legs,’ she said.

The animals understood what she wanted and so with her left hand gripping Brock’s front leg as he stood at her side and with the weight of Sam holding her down she threw the cape out with her free hand, but it did not fall straight and dropped well short of Nab’s clutching hand.

‘Hurry,’ he shouted and as he did so he felt the sludge force itself up over his waist.

Beth drew her right arm well back so that the cape was stretched out straight on the path behind her and then with all the strength she could muster she flung it out across the bog. This time the whole of its length was used up and her arm lay out at full stretch. With her heart pounding beneath her she hardly dared raise her head to look, but when she did, to her enormous relief, she saw that he had just managed to grasp the end. Then she could feel him pulling on the cape and her arm felt as if it was being torn out of its socket. She closed her eyes and gritted her teeth as a wave of pain swept over her. The problem now was how to haul him out of the bog. She tried to bend her arm to pull him but it was impossible; she did not have enough strength. Then she felt her hand begin to slip on the cape but she managed to wedge her fingers against the lion’s-head buckle to stop it sliding. Next she began to wriggle back on her tummy in an attempt to drag him out but that also proved impossible. Desperately she thought for a second and then she called to Brock and Sam to grab hold of her by her legs and pull. They did so, gripping her jeans in their teeth and pushing away from the edge with all their strength. At first nothing happened but then slowly, inch by inch, Beth felt herself moving back.