“My soul is created as if in the image of Russian icons.”

Stairs as a symbol of Christ’s suffering appear in the Catholic tradition as early as the 9thcentury and is found in icons, crucifixes and retablo. And although the presence of a ladder in “Ascension to the Cross” and “Descent from the Cross” is not mentioned by any Gospel – ladders first appeared in illustrations and images – ladders are often mentioned in theological manuscripts from the Middle Ages. One can even speak about the formation of established medieval iconography in the image of Christ climbing a ladder to the crucifix, an example of which we see in the illustration by Pacino di Buonaguida to the c. 1320 manuscript “Vita Christi” (V1: 102). In Fra Angelico’s “Nailing of Christ to the Cross” (1442) (V1: 106), both executioners and Christ are depicted on ladders leading to the cross. Thenceforth the ladder is frequently an attribute of execution. For example, Jan Luyken’s 1685 etching, “Anneken Hendriks, tied to a ladder and burned in Amsterdam in 1571” (V1: 119), depicts the execution of a woman condemned for heresy. Here the ladder itself, in an analogy to the cross, is the instrument of execution.

Among contemporary artists, Richard Humann developed this theme with a neo-conceptualist twist in his 2008 installation “ You Must be This Tall” (V1: 114–116). The artist explores the collective subconscious through a projection onto everyday objects in a miniature amusement park. And apparently innocuous, at first glance, children’s attractions turn out to be modified to serve for executions.

Thus, we can talk about the ambivalence of the image of stairs and ladders, now uplifting and sacred, now aggressive and destroying; they are often encumbered with elements contrary to their practical nature. Stairs or ladders, helpful tools that accompany a person on his path, can be transformed into obstacles blocking that path. The materials, stairs or ladders are constructed from, can evoke associations with physical pain, communicating an aggressive message and a danger sign.

The Cuban artist Kcho (Alexis Machado) expresses this ambivalence in his 1990 installation, “The Worst of All Traps” (V2, p. 215). His ladder’s frail wooden frame suggests that it would make easy prey for enemies, but the rungs are made from machete blades – symbols of the Cuban war of independence. The artist’s use of palm branches – the national tree of Cuba, strengthens the already obvious allegory and ensured that the work attracted broad attention in Cuba. Nevertheless, Kcho asserts that the materials do not dominate the installation, but rather help the viewer find meaning in their very physical essence.

Unlike Kcho’s rusty machetes, which recall Cuba’s history but pose only a metaphorical threat, the sharpened steel knife-steps in Marina Abramovic’s 1996 installation “Double Edge” (V1, p. 126–127) can cause real physical harm. Here, as in much of her work, Abramovic examines the limits of physicality, provoking in the viewer an emotional involvement on the level of reflex. The work consists of four ladders with rungs made of different materials – from ordinary smooth wood to knife blades, heated metal and icy rails. The sight of these ladders whose familiar form has been transformed into something dangerous causes psychological discomfort in the viewer. These “dangerous steps” are a metaphor for trials that have to be overcome by overcoming mental and physical fears. In the museum setting, this installation did not involve physical contact, but in 2002, Abramovic revisited the ladders in her performance piece, “The House with the Ocean View” (V1, p. 124–125). For twelve days the artist lived in specially built minimalist rooms, open for viewing by visitors to the gallery. Under these conditions, ordinary actions take on the ritual character of a trial, a test combining asceticism and total publicity. Ladders with knives for rungs physically prevent the artist from going beyond the allotted space, thus an inanimate passive object becomes an actor in the performance, demonstrating its power over the will of the artist.

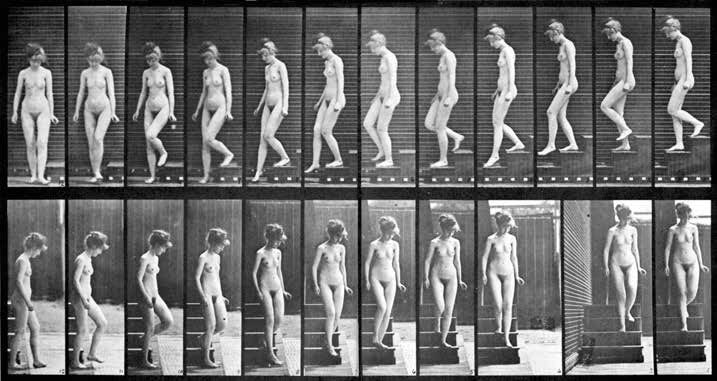

Eadweard Muybridge, Woman Walking Down Stairs, Chrono-photography, 1887

“For ‘The House with The Ocean View’ it was very difficult to be in the present constantly for twelve days, so I always tried to stand on the edge, over the ladder with knives, where I might fall on the knives.”[6]

In another project, “The Abramovic Method” (2016), at the Benaki Museum in Athens, the viewer becomes part of the performance that takes place on a gently sloping ramp that connects floors of the museum on the way to the main exhibition space. The artist has deliberately chosen a space in the museum that is usually considered secondary, to be passed through quickly. Participants in the performance are forced to move in slow motion, concentrating on a more profound consciousness of their bodies in time and space; this is particularly noticeable in contrast to the movement of other visitors to the museum. In this way, Abramovic induces the viewers to focus, through body experience, on a specific “episode” of life.

Artists began to portray movement on stairs in painting at the end of the 19thcentury. Marcel Duchamp’s famous 1912 cubist painting, “Nude Descending a Staircase” (V1, p. 183), which The New York Times christened “Explosion at the Tile Factory”, depicts a woman’s motion down five steps along a spiral staircase through the successive overlapping of individual fragments. The painting was inspired by the new technology of cinema and particularly by Eadweard Muybridge’s famous series of photographs “Woman Descending Stairs”, made in 1887.

Gerhard Richter’s “Ema. Nude on a Staircase” (V1, p. 185), painted in 1966 is a comment on Duchamp’s work. Like Duchamp, Richter based his painting on a photograph. The model was the artist’s wife, descending an ordinary staircase devoid of details that would indicate a particular time. Richter’s almost ghostly image, seemingly woven of dreams and memories, renders Duchamp’s experiment to the limits of traditional portrait painting, a genre much out of favor in the art world of the 1960s. Richter’s painting later served as an inspiration for Bernhard Schlink’s 2014 novel, “The Woman on the Stairs”.

The phenomenon of movement both up and down steps is the subject of Mario Ceroli’s sculpture “La Scala” (V1, p. 186). His staircase with profile cut-outs of men and women, made of unpainted wood, captures the various phases of this movement, focusing on the contrast of static and dynamic. In her live installation “Plastic” (2015–16) by the artist and choreographer Maria Hassabi explores the same dichotomy of static and dynamic, examining pauses both plastic and temporal in a museum space. Hassabi placed performers along the flight of stairs lying perfectly still, contrasting sharply with the rapid flow of visitors around them. Thus, the artist expands our idea of the obviously utilitarian significance of the stairs in the museum, slowing down the rhythm of our reaction to its meaning.

“This is a transition space. For this reason, I was interested in presenting the work there (on the stairs). How can transitional space become a pause? Thus, the movement of stairs has a very forward direction to it. It’s falling forward.”[7]

Maria Hassabi, Plasticity, performance, 2016, Museum of Modern Art, New York